This project-based high school serving 30 districts has endured for nearly two decades with a focus on STEM

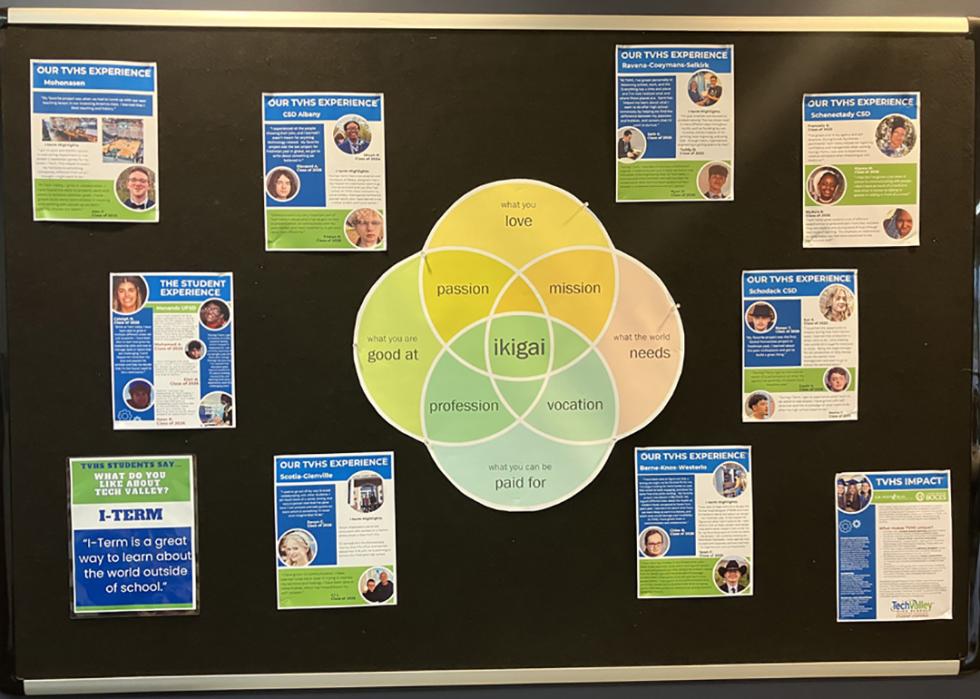

Once a year in the winter, all classes stop for a week so students can take part in a schoolwide "I-Term" that matches them with community partners to explore careers. Like much of the curriculum, the project is guided by the Japanese principle of "ikigai," or purpose. It asks students to consider not only what they love to do and are good at, but what the world needs and what they might someday do well enough to earn a living.

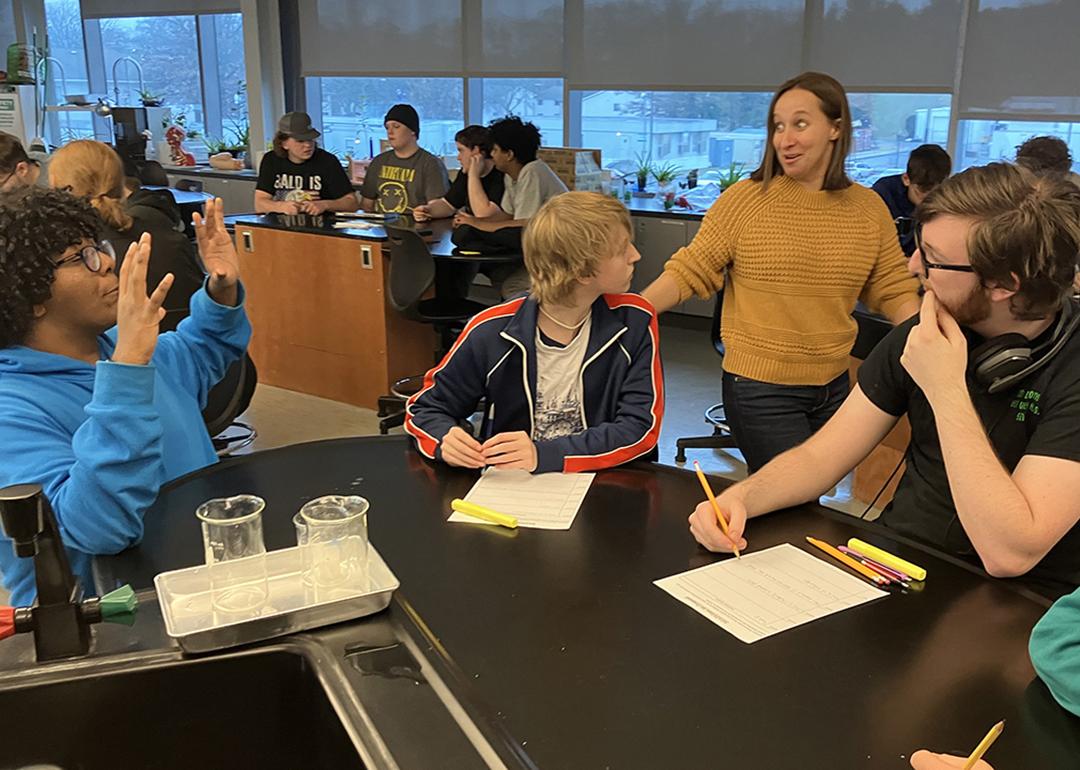

As freshmen, students explore openly, Hawrylchak said — many freshman boys take this opportunity to shadow game designers at local studios, for instance. But by sophomore year, teachers are asking them to think more holistically about their purpose. "We're saying, 'O.K., now we want to add the layer of: What are you good at?'"

It gets more complex: As juniors, they must confront not only their tastes and abilities, but whether the world needs what they have to offer — and how they can make a living doing it.

Pretty soon, Hawrylchak said, "They're aware of this entire Venn diagram" that encompasses a larger sense of purpose. That's when they begin job-shadowing for a week as juniors. As seniors, that becomes a two-week commitment, offering "a deeper, richer experience," she said.

It all leads to a lot of soul-searching, with students often taking years to narrow down their ideas. One student who loved soccer spent her first I-Term shadowing soccer coaches at both the high school and college levels, then developed an interest in politics and worked in a state senator's office and, later, for a legislative lobbyist. She eventually attended the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, intending to study politics.

"My deepest hope is that the kid exits high school with a sense of maybe, 'These are some things I don't want to do,' " Hugger said. " 'These are not things that inspire me or make my heart beat fast. And maybe here's the thing that I do want to do.' "

'The more times I do it, the more skills I learn'

Each fall, seniors spend about six weeks on a capstone project in which they partner with a local business — given the region, that can mean anything from a small advertising studio to IBM or State Street Bank.

Students take a day to "speed date" with company representatives and figure out which one they want to work with. Then they settle in and work out solutions to a problem the company presents.

For one group this winter, the challenge was to design soundproofing surfaces for a makerspace in nearby Troy. DuBois, who wants to study engineering, designed a chandelier that absorbs sounds and a gaming surface that turns into a moveable, soundproof wall, while a classmate proposed panels filled with homegrown mushrooms that absorb sound.

Butler recalled that she was an abysmal public speaker when she arrived at Tech Valley as a freshman. She would cry, laugh — or both — when called upon to make a presentation. Four years later, she is now quite comfortable in front of a crowd. "The more times I do it, the more skills I learn. You get better at it."

After graduation this spring, she's hoping to study education or museum curation at a nearby state university campus — she has always loved wandering through museums, ever since she visited one that her grandmother cleaned.

Her previous school couldn't come close to what Tech Valley offered: 100 community service hours, working with business partners, job shadowing.

"I wanted to go [here] because they said that you get to go out on your own, discover who you want to be, what you are going to be," she said. "Instead of just sitting in traditional classes and people talking to you about their careers, you got to experience that."