You look like a Michael: What research shows about how names shape your life

Editor's note: The Social Security Administration collects data on baby names based on a binary understanding of sex and gender; however, we recognize that names aren't inherently gendered.

Varnum became interested in studying naming trends because public naming records were available, and they could help answer elusive questions on "more direct psychological measures, like individualism or conformity." In contrast, data from traditional measures, like questionnaires or experiments, may be limited in time or scale.

"In my work, I've shown, for example, that people are less conformist in their naming practices in places that were more recently frontiers," Varnum said. In addition, "Within the U.S., a decline in the frequency of people receiving popular names over the past century or so appears linked to things like rising levels of wealth and decreasing pathogen threat." He suggests these factors may encourage people to pursue autonomy and uniqueness more.

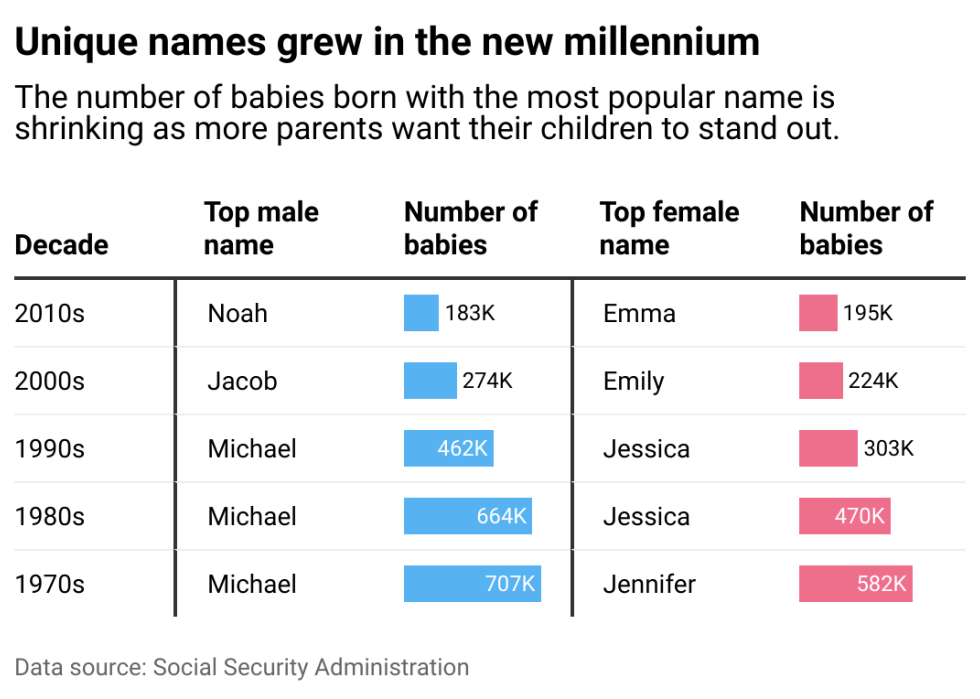

Whatever the explanation, parents in the U.S. seem to be increasingly favoring names that might help their child to "stand out" from their peers. At the same time, gender-neutral names have also become more common, starting to rise in popularity in the '90s, according to Names.org.

Michael, while no longer king for boys, was still a respectable #7 in the 2010s and #2 in the 2000s. Some parents still favor tradition over novelty. Curiously, the same cannot be said for the most popular girls' name for three decades leading up to 2000—Jessica, which fell to #175 in the 2010s.

And then there are the names that, in the popular imagination, have become insults: the memeable monikers of "Karen," "Chad," or "Kevin." Varnum explains, "People with names that are currently disliked in the U.S, like Chad or Karen, probably bear some of the weight of the negative stereotypes and associations folks have with those names. And prior work does find that we feel more warmly, for example, towards Elizabeths than Mistys."

Rightly or wrongly, names are a type of shorthand for expressing a sense of self, establishing connections, marking national and ethnic affiliations, and becoming targets for stereotypes and prejudice. For instance, Varnum said, "People sometimes also assume that those with names more common in African American communities might be of lower status or less competent."

Aaron Hall, CEO of the San Francisco-based branding company Emphatic, recently wrote about the connection between baby naming and company branding: "Naming a baby is a joyous, significant event. By applying some tried-and-true branding principles, you can approach the process with confidence and creativity."

Offering the caveat that he hasn't personally named a human, Hall nonetheless said landing on the right name, be it for a baby or a company, can be a fraught and stressful process. "It's important for that baby and brand to develop their own sense of self and characteristics that define who they are," Hall told Stacker. "The name doesn't have to anchor them to the original intent or connotations."

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Elisa Huang. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.