Why has an entire generation been shut out of the housing market?

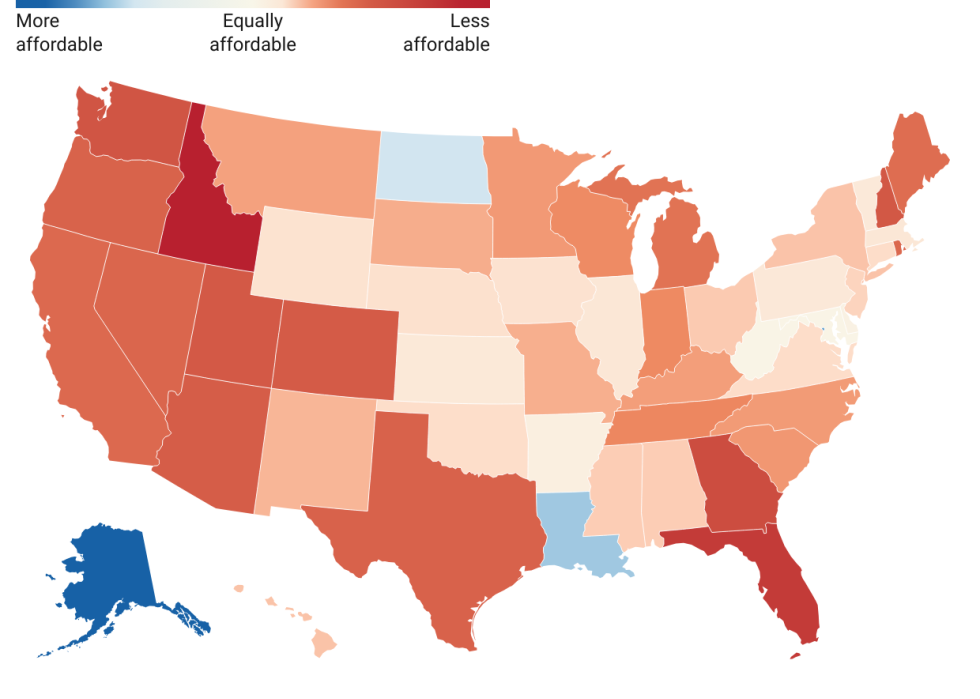

Affordability isn't just about the price tag of a home. It's about how much people are earning. In 2023, U.S. home values in every state were at least 2.5 times higher than the annual household income. In 16 states, home values were more than 5 times the annual income. This is a major uptick from 10 years earlier, when only two states—Hawaii and California—had ratios that high.

Even in states where affordability didn't get significantly worse, it's often because the home-to-income ratio was already bad in 2013 and it has simply stayed that way. For instance, home values in Massachusetts went from 4.9 times the annual income to 5.5 times. That means affordability only got 12% worse—a silver lining for one of the most unaffordable states in the nation.

The affordability crisis has spread across the country. Only three states (Alaska, Louisiana, and North Dakota) have become more affordable over the past decade, but all by less than 15%.

Home ownership didn't suddenly become unattainable. The affordability crisis is the result of a series of economic circumstances and events that have compounded over time—a period of time that now stretches generations.

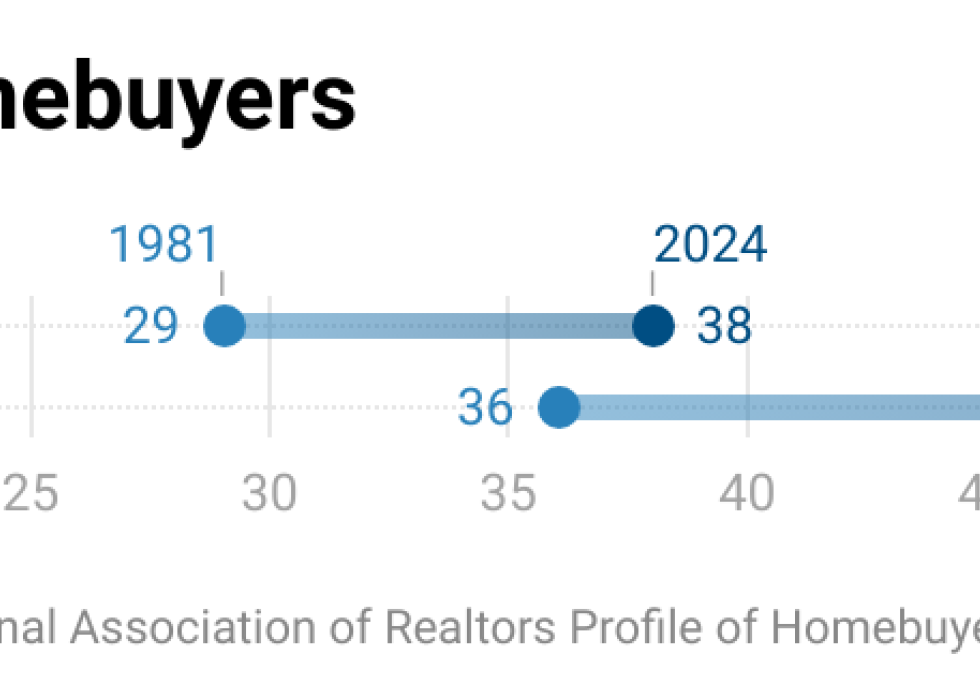

Today's first-time homebuyers are typically 38 years old, according to the National Association of Realtors. Back in 1981, they were 24 years old. That's nearly a 15-year difference.

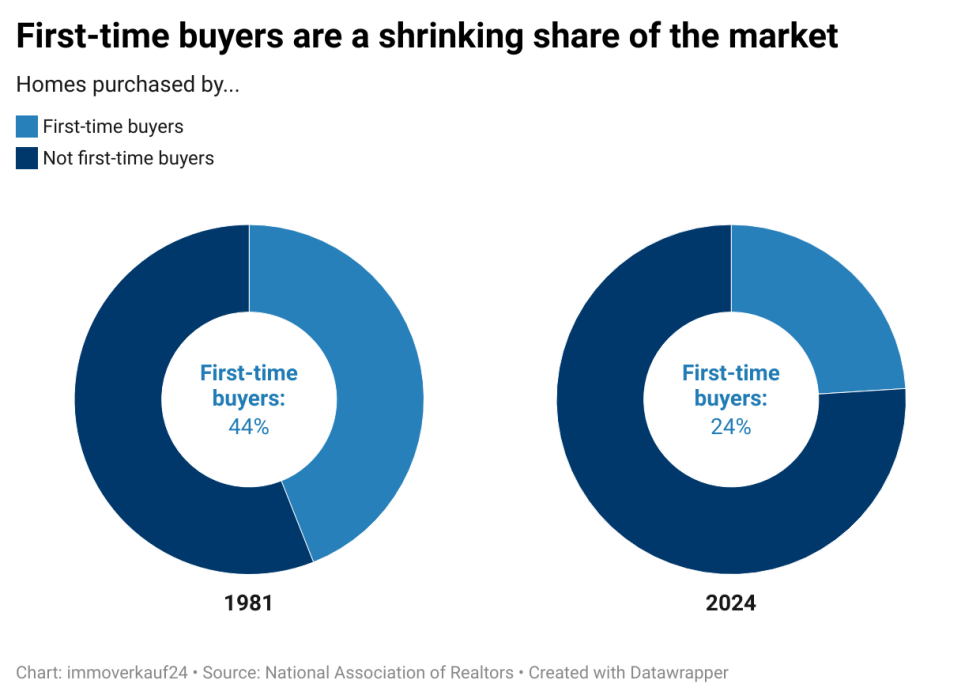

Not only are first-time buyers older, they tend to make up a smaller share of home purchasers. Only 1 in 4 homes sold last year went to first-time owners. Back in 1981, first-timers made up close to half of all sales.

It's hardly a wonder that there are so few first-time homebuyers—and that they are on the cusp of being middle aged—if you look at the economy and the real estate market over their lifetime.

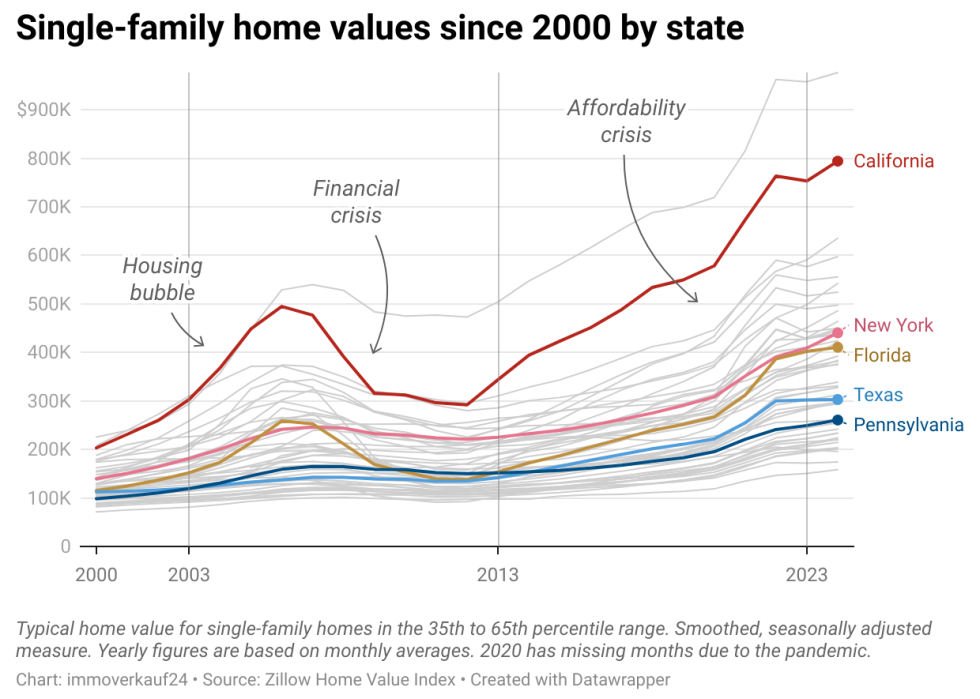

A 38-year-old who purchased a home in 2024 was only 18 in 2004. That was right when home prices were beginning their explosive climb. Four years later, the crash happened. Home prices plummeted as the real estate bubble burst and took the rest of the economy with it. Today's 38-year-olds who attended college were graduating at the time, and were facing a dismal job market. What's more, many of them were saddled with student loans. Saving for a down payment felt unattainable.

By the 2010s, when the real estate market began to level out, the damage was already done. Many people of that generation had been shut out of the market.

By the end of the 2010s, home values were on the upswing again, and when the pandemic hit in 2020, there was a frenzy in the market. Homes were selling over asking price, resulting in bidding wars.

The problem for the same would-be buyers now is that higher interest rates have kept many current homeowners from selling. A recent market report from J.P. Morgan suggests that the situation won't improve until rates drop to 5%, which likely won't be the case for at least another year. With less inventory, prices continue to rise—and they are rising much higher than wages. The market is stuck. And so are the people trying to enter it.

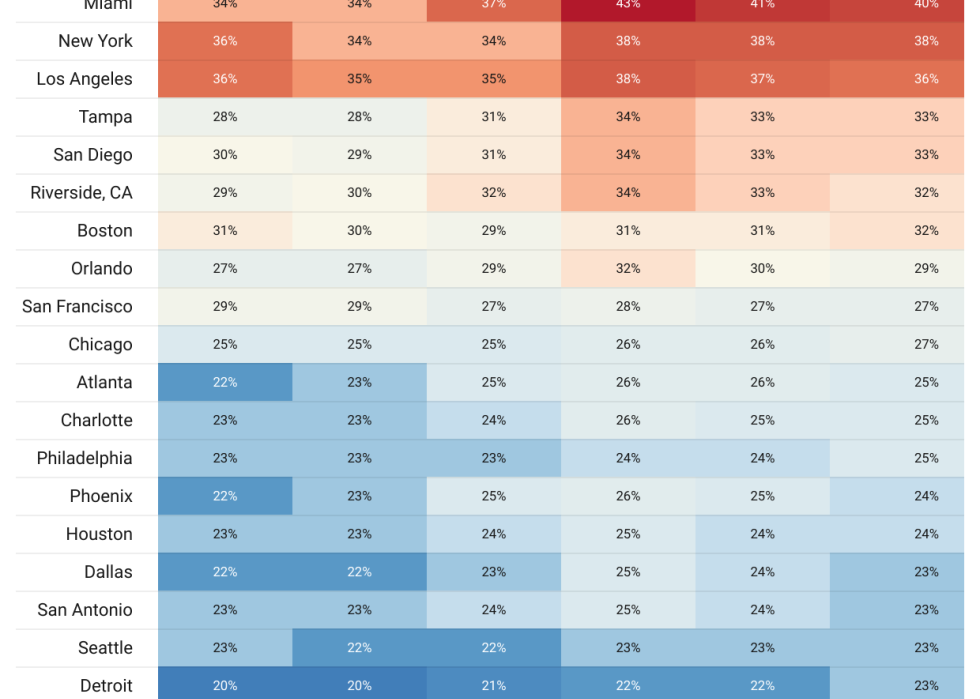

As home ownership slips out of reach, many Americans are relying on rentals for housing. But rental prices are also extremely high compared to wages. According to Census data, over 21 million households spent more than 30% of their income on rent in 2023. That's half of the 42.5 million renter households in the United States.

Some places have extremely unaffordable rental markets. In Miami, renters spend 40% of their income on housing. In New York, it's 38%, and in Los Angeles, 36%.

More than half of people who want to buy their first home say their existing living costs are too high and their incomes too low to afford a down payment and cover the closing costs of a purchase, according to a Bankrate survey published in 2024. Another 18% also cited credit card debt and 10% cited student loan debt as obstacles that are keeping them from affording a home.

The result: People are continuing to struggle to set money aside for a down payment.

No easy fix

The data helps explain why the housing market feels so broken for so many people. If the past decade is any indication, there is a growing gap between what people earn and what homes cost. And while every state is different, the story is largely the same: Prices have surged, wages haven't, and fewer people can buy.

One way to alleviate the pressure in the market is to have more housing options available. Freddie Mac, which facilitates the mortgage market by buying mortgages and selling them to investors, noted that there was a shortage of 3.8 million housing units in late 2020. By 2024, that shortage still stood at a staggering 3.7 million units. States are actively trying to make it easier to build more housing, by revising zoning regulations, streamlining administrative processes, and incentivizing construction of more affordable housing options.

But the bottom line is that the housing crisis didn't happen overnight—and it won't be solved overnight either.

Methodology

To see affordability changes over time, the research team gathered historical data on incomes and home values by state. Median household income came from the U.S. Census Bureau and home values came from the Zillow Home Value Index (ZHVI) for single-family homes. The Zillow data was monthly, so the team averaged the months of each year for which data was available (typically, 12 months, except in 2020, which had less data due to the pandemic).

The team calculated the income-to-home-value ratio for each state in 2013 by dividing household income by the home value. They repeated that step for 2023. Finally, they measured the percent change of that ratio to show how affordability has improved or worsened in each state. If the change was within ±3%, the state was considered to be unchanged (equal affordability in both years).