What state seals say about America and what they don't

While many state seals carry patriotic elements akin to those on the "Great Seal," no two are exactly alike. Not all of them, for instance, carry a Latin motto—though many do, like New York ("Excelsior" meaning "ever upward"), Idaho ("Esto perpetua" for "let it be perpetual"), and Virginia ("Sic semper tyrannis" meaning "thus always to tyrants"). Still, many common themes tie them together.

State symbols frequently take center stage on the state seals—as animals (California's grizzly bear, New Jersey's horse), birds (Louisiana's brown pelican), flowers (Idaho's Syringa), and even trees (Indiana's tulip poplar, South Carolina's palmetto tree). Those are just a few examples of natural beauty depicted on the state seals, which also include natural phenomena like the northern lights (Alaska), geographical features like the Mississippi River (Iowa) and the Rocky Mountains (Nebraska), and in the case of the Sunshine State of Florida, rays of sunlight.

In some cases, Native Americans are shown tending nature—whether it's herding the American bison on the North Dakota and Kansas state seals or scattering flowers like the Seminole woman does on the Florida seal.

It's not uncommon to see historical pioneer scenes colliding with evocations of the industrial age and agriculture intermixed with commerce. The Nebraska seal, for instance, shows a combination of images referencing agriculture (wheat, corn) and the mechanic arts like blacksmithing (a crucial skill on the frontier during the homesteading era). Farming and mining are represented equally on the Montana state seal, as both industries continue to contribute to the state's economy even today. Alaska's seal bears a farmer, horse, and shocks of wheat to represent agriculture alongside a smelter to represent its still-active mining industry.

Amid those uniquely "New World" scenes, you'll also find many state seals showing classical influences from the Old World. In addition to the mottos in Latin and Greek (like California's "Eureka"), there are also Greco-Roman figures like Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom (California); Spes, the Roman goddess of hope (South Carolina); Ceres, the Roman goddess of grain (New Jersey); and Virtus, the Roman goddess of bravery (Virginia). Other Eurocentric elements include Roman numerals, as on the Wyoming seal, and even Greek architecture, like the Corinthian columns found on the state seals of Georgia and Wyoming.

There's a lot of symbolism packed into many of these state seals, but looking at them through today's lens, it becomes clear some don't portray a comprehensive history or an inclusive current identity. For instance, the landscapes shown on the seals often depict a more idyllic, rural past rather than the urban areas and modern cityscapes that may characterize the states today.

Many state seals also strongly feature male figures—either in positions of prominence alongside women (an intentional decision, according to the artist of Idaho's state seal) or without any women at all.

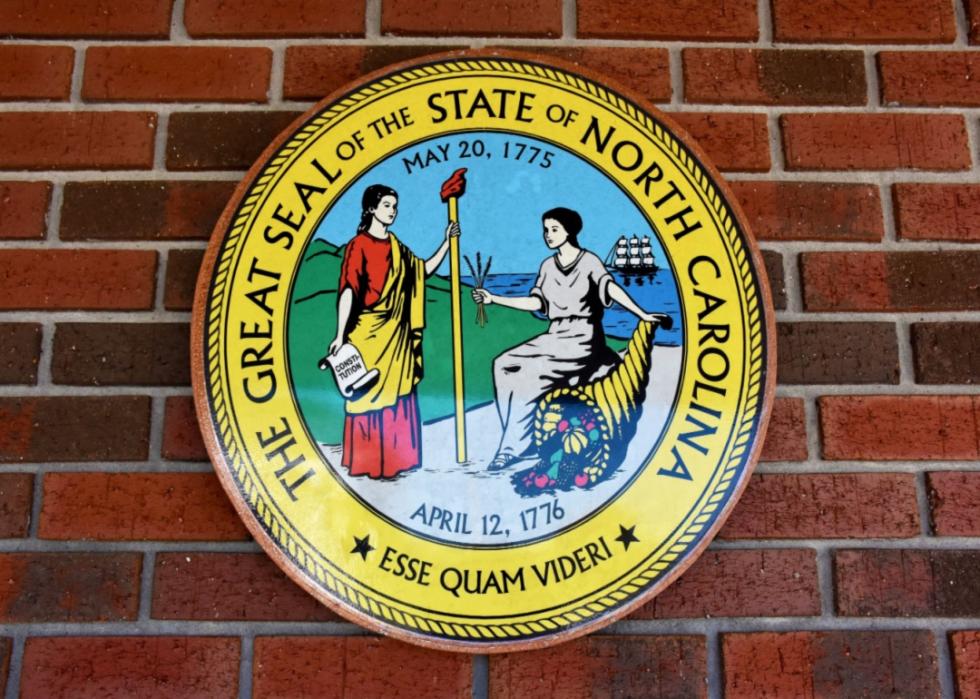

When female figures are present, they're frequently relegated to allegorical roles. Idaho and New York's state seals feature a rendition of Justice, while North Carolina, New York, Arkansas, and Hawai'i feature the personification of Liberty (sometimes known as "Lady Liberty").

State seals rarely depict racial and ethnic groups, despite the significant contributions made to state histories by historically excluded groups like Black Americans and Asian Americans. In some cases, the presence of Indigenous Americans is dehumanized—represented only by the symbolic presence of weapons, like the 17 arrows on the state seal of Ohio.

Such omissions mean the seals don't necessarily represent the diverse populations of its past—especially when considering that some of these seals were originally created more than 200 years ago (and in the case of Pennsylvania, predating its own statehood). They also don't capture the modern realities of states today. Nevada's seal does not mention the thriving tourist destination Las Vegas has become, and it shows no indication of its cultural diversity (with the 15th-largest Latino population in the U.S.).

State seals may seem like a permanent fixture in local governments—a fixed, enduring symbol of the past. But in reality, some seals have evolved and adapted to changing times.

The Great Seal evolved throughout history under the leadership of three different committees that later added the olive branch, the constellation of 13 stars (representing the original 13 colonies), and the bald eagle. Likewise, the North Carolina state seal has undergone multiple iterations, starting with an original (but unofficial) pre-Revolutionary War design and subsequent variations that weren't standardized until 1971.

Washington state has used more than two dozen variations of its original seal design, with George Washington at the center. The current insignia was settled upon in 1967, but even that one may not last forever.

Some seal redesigns continue to happen today. Minnesota officially adopted a new state seal in 2024, foregoing the French motto "l'étoile du Nord" ("the star of the North") for the Dakota language phrase that the state traces its name back to, "Mni Sóta Makoce" ("Land of the sky tinted water"). The new Minnesota design—chosen out of 400 public submissions—also abandons its former anti-Native American bias, replacing a pioneer scene with an image of a red-eyed loon (the state bird), wild rice (the state grain), Norway pines (the state tree), and waves representing the state's many bodies of water.

Massachusetts has been trying to redesign its state seal since 2021. However, Indigenous leaders have been complaining about the 19th-century-era design and its violent portrayal of a Native American man standing under a white colonist's sword-wielding arm—for over 50 years.

There's no shortage of possible ways to reimagine any of the states' seals—for example, by incorporating historically significant groups like Black civil rights leaders and politicians, Chinese railroad workers, Filipino labor leaders, or Japanese farming communities and fishing villages. Perhaps new state seals could look to the present or future for inspiration instead of solely looking to the past. (Rockets and other spacecraft for Florida or Texas, anyone?)

Still, bureaucracy frequently moves at a snail's pace. While cultural shifts tend to happen incrementally, governments have shown that it could take years—if not decades—to precipitate transformative legislative change.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.