Americans with disabilities work remotely more than the general population in some states. Here's how South Dakota compares.

The remote work wave has not reached workers with disabilities equally across the nation.

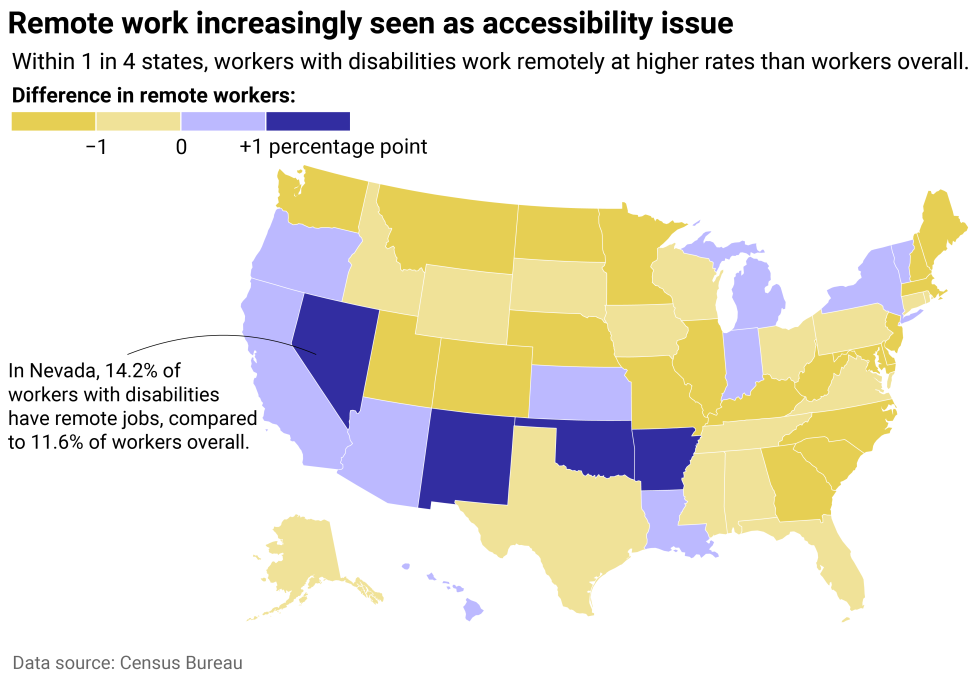

In most states, a smaller share of workers with disabilities have remote jobs compared to the rate for workers overall. In Colorado, North Carolina, and the District of Columbia, remote work rates for all workers and those with disabilities surpass national averages—quite substantially in the latter two. Workers with disabilities also have higher workforce participation rates in Colorado and Washington D.C., potentially meaning more workers in nonremote-capable roles.

However, in 13 states, workers with disabilities have remote jobs at higher rates than workers overall. The difference is striking in a few of these states. In Nevada, workers with disabilities lead the overall working population in remote jobs by 2.6 percentage points. Workers who report having disabilities in New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Arkansas also work remotely at notably higher rates.

Interestingly, these states' overall work-from-home rates are lower than the national average. In these cases, remote access at work may be limited and potentially reserved for those with accessibility needs. For instance, in Nevada, the state government issued new guidance in December 2023 specifying that for agency employees, "remote work is the exception, not the rule." The rule provided that remote work agreements would be approved individually and not applied across entire departments, divisions, or other broad categories—limiting remote opportunities for workers.

While this particular guidance only applies to state government workers, it reflects a broader work culture that is less remote-friendly. Allowing individuals with disabilities to work at home is one type of reasonable accommodation, required by the Americans with Disabilities Act for employers with 15 or more employees. In turn, remote work remains a viable option for employees with disabilities as an exception to otherwise tight restrictions on remote work.

Importantly, not all workers with disabilities want remote jobs or to work in roles suitable beyond the physical workplace. Working remotely can cause isolation and loneliness. For people with disabilities, who already face disproportionate stigma and exclusion in social settings, these effects can be particularly damaging.

Still, remote work offers myriad benefits for workers with and without disabilities alike. It can potentially promote equity and inclusion—especially when executed with the proper tools, practices, and normalization, rather than treated as a one-off accommodation.

Read the national analysis to see how other states compare.

This story features data reporting and writing by Paxtyn Merten and is part of a series utilizing data automation across 50 states and Washington D.C.