Going to extremes: How Olympians vying for the gold in Paris contend with climate change

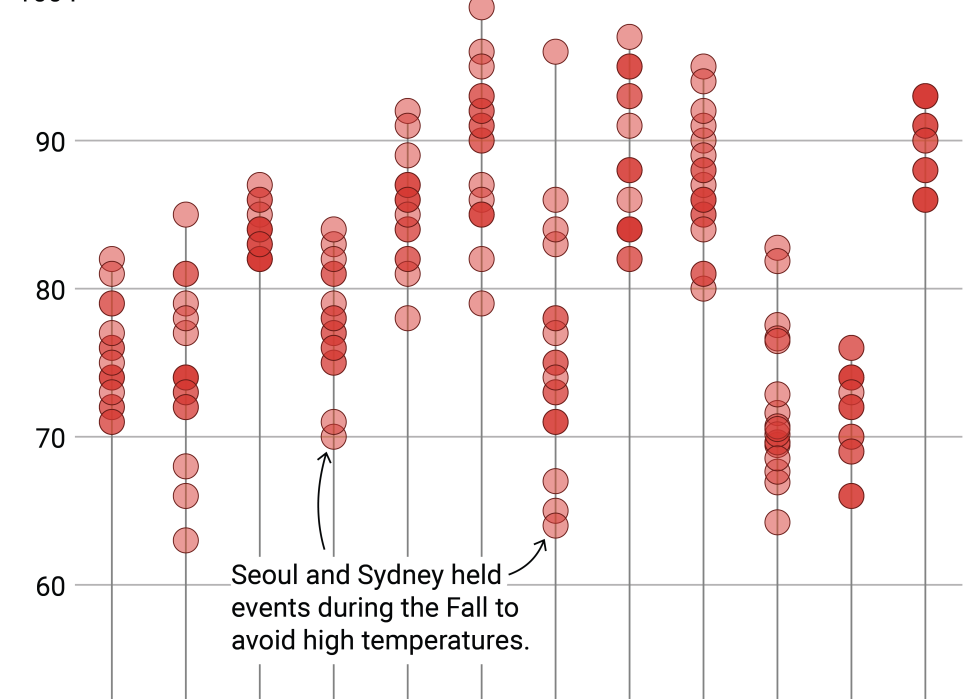

Due to the Summer Olympics taking place during the hottest months for most host cities, organizers regularly have to factor heat into their planning. The exceptions are cities in the Southern Hemisphere, such as Sydney (2000 Olympics host) and Rio de Janeiro (2016 host), which welcome cooler temperatures during the Northern Hemisphere's summer months.

During the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, heat and humidity took a toll on athletes, spectators, personnel, and animals. Temperatures reached the upper 80s even for evening events, like the women's marathon. The winning time was nearly 8 seconds slower than the first women's Olympic marathon in 1984. Horses also struggled in Barcelona's climate, leading researchers to examine the effects of heat and humidity on horses.

A number of changes followed, and by the time Atlanta hosted in 1996, organizers moved start times to the morning, implemented mandatory breaks, and used rapid-cooling techniques on horses to prevent heat-related illnesses in the animals.

Summers in Tokyo are notoriously hot and humid, which made the Tokyo 2020 Olympics more difficult for athletes. "When you increase the moisture in the atmosphere, it takes more energy for your body to sweat," Craig Ramseyer, assistant professor in the geography department at Virginia Tech, told Stacker. "It's not as efficient, and you store that heat internally for longer." Prolonged exposure to extreme heat and humidity can cause dehydration, fatigue, cramps, heat exhaustion, and even heatstroke, which can damage a body's organs and even cause death.

During the Tokyo Games, 110 athletes suffered heat-related illnesses. The tennis matches were particularly brutal: Spain's Paula Badosa retired from her quarterfinal match due to the heat, leaving the stadium in a wheelchair and covered in a cooling towel. Russian player Daniil Medvedev took medical timeouts in an early round match to cool down.

Organizers in Tokyo scrambled to make adjustments to create safer conditions for athletes, even relocating marathons and race walks more than 500 miles north to Sapporo in the hopes of cooler temperatures. Unfortunately, a heat wave in Sapporo meant race day temperatures weren't much better than in Tokyo.

Even with the extreme conditions, Olympians pushed themselves to their limits. In testimony for the BASIS and Frontrunners report, New Zealand medalist Marcus Daniell said of the Tokyo games, "At the time I felt like the heat was bordering on true risk—the type of risk that could potentially be fatal. One of the best tennis players in the world [Medvedev] said he thought someone might die in Tokyo, and I don't feel like that was much of an exaggeration, especially when you're playing for your country and the desperation to perform is running through your veins."

While lessons from Tokyo may inform the heat management approach in Paris, a different city brings new challenges.

In Paris, zinc-roofed buildings and limited public green space (just 10% of the city) create what researchers call an urban heat island. "There's been an increase in moisture in the atmosphere and in Paris," Ramseyer told Stacker. "And in places in Europe that get a lot of moisture out of the Mediterranean, for example, are not only warmer than they used to be, but much more humid than they used to be, and so that's really concerning when you think about the Olympics being in Paris."

According to NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information, 2023 proved to be the hottest year on record, and 2024 is on track to do the same. Europe is the fastest-warming continent on the planet; each of the 12 months since June 2023 was the hottest on record, according to the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service.

The effects of extreme heat have been dire: Places like New Delhi and Greece have reported heat-related deaths in the summer months this year, and more than 1,000 people died in June during the Hajj, the annual pilgrimage for Muslims to Mecca, when temperatures peaked around 125 degrees.

In an effort to lower its carbon footprint, the 2024 Games sets a sustainability gold standard

While the model of the Games hasn't really changed, University of Toronto professor Madeline Orr noted that some resource-intensive hosting elements have included using existing venues instead of building new ones and thinking more about energy usage, waste, and procurement.

The International Olympic Committee recognizes the role of the Games in climate change and is working to build a more sustainable future for the Olympics. The committee has aligned with the Paris Agreement to tackle climate change, and also put a cap on the number of participating athletes in an effort to curb the carbon footprint of the Games. Paris 2024 plans to welcome about 10,500 athletes from 184 countries—over 900 fewer athletes than Tokyo 2020. However, it's still far more than the last time Paris hosted the Olympics in 1924 when just over 3,000 athletes competed.

Orr explained that coaches, support staff, and hundreds of thousands of fans contribute to a much larger carbon footprint. "That's the big problem because that fan travel is fundamentally the biggest challenge in the current model, and nothing about how hosting is happening is addressing that."

Paris is using existing or temporary infrastructure for 95% of the venues needed for the 32-sport program, taking advantage of already-constructed venues nationwide. The city built two new sports venues and the athletes' village; organizers used sustainable construction methods and installed recycled materials, such as seating made from recycled plastic. Policies were also developed to cut carbon emissions by using more plant-based ingredients and sourcing food within a 250-kilometer radius (about 155 miles).

"For a really long time, the idea was you build the city to meet the needs of the Games," Orr said. "And now we're thinking about building the Games to suit what's already in the city."

Spectators can bring reusable water bottles into venues, which will not sell single-use plastic bottles. In a more controversial move, the Olympic Village for athletes was set to use a geothermal cooling system and fans instead of air conditioning. After an outcry from many athletes, the U.S. and at least eight other countries plan to secure AC for its athletes, and organizers ordered 2,500 air conditioners for the village.

If Paris 2024's sustainability measures prove successful, it could set a precedent for future host cities. Still, the challenges a warming climate poses to athletes are only growing.

What does the future hold for Olympians?

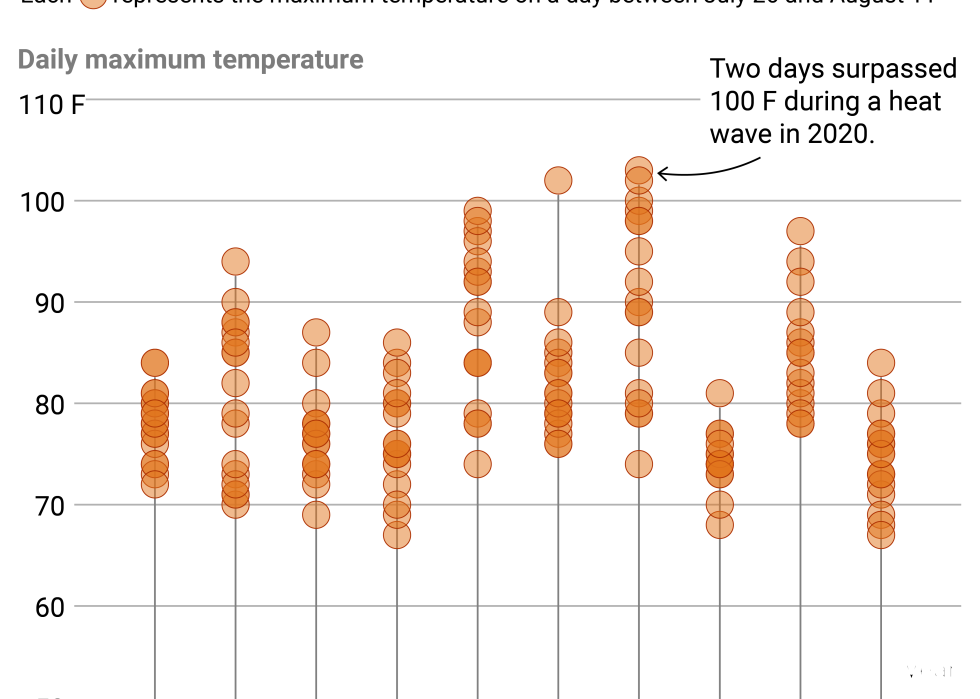

The 2028 Summer Olympics will be in Los Angeles, another urban heat island. In July, a heat wave in the region pushed temperatures past 100 degrees. Organizers for those games have already implemented a venue plan that calls for no new permanent venue construction, continuing hopes that the Olympics can shrink its carbon footprint in alignment with the IOC's agenda.

Aggressively sustainable venue plans, water refill stations, and other carbon-curbing measures are all practical solutions. However, these stopgap measures won't ultimately protect future Olympians from the mounting effects of climate change. As temperatures continue to climb, the grueling training modifications, long-term impact on the body, and potential health risks of heat exposure will make elite athletics even more demanding—and riskier. For now, winning or losing may hinge, in part, on learning to compete in and recover from extreme heat.

With the Paris Games underway, attention will soon turn to Los Angeles. Four years from now, let's hope a race or a match is all that athletes stand to lose.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Nicole Caldwell and Paxtyn Merten. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.