Climate change is messing with city sewers—and the solutions are even messier

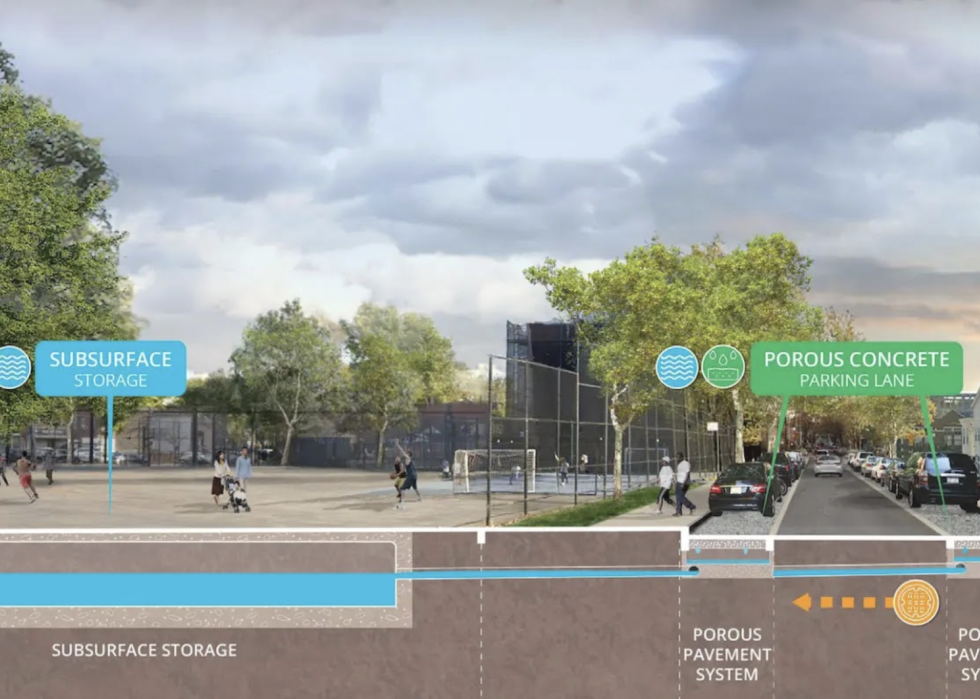

In early 2023, the city unveiled plans for $84 million worth of Cloudburst infrastructure at eight public housing developments, including sunken basketball courts that can capture stormwater in the event of heavy rain. It also announced additional, larger Cloudburst initiatives funded by $390 million in capital funds in four focus neighborhoods in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens. These areas were chosen based on several factors: history of flooding, future inundation risk via modeled stormwater flood maps, and socio-economic vulnerability.

Alexx Caceres is a native of East New York, one of the four focus neighborhoods, and works as the farm manager of East New York Farms. Caceres says they welcome the planned infrastructure. During the storm last September, the front of Caceres' farm was inundated. They hope that the Cloudburst infrastructure will help to prevent subsequent sewer overflows and floods.

"They are trying to create infrastructure that holds the water in," Caceres said, "giving the sewage system time."

Other peripheral Cloudburst initiatives in Staten Island and the Bronx have sought to restore natural drainage corridors that have been built over by urban developments.

While effective in creating more pathways for stormwater to flow out of the city, these projects may be less feasible in more population-dense boroughs such as Manhattan, according to Daniel Zarrilli, the chief climate and sustainability officer at Columbia University.

The New York City Department of Environmental Protection declined to comment on its plans to manage flooding.

Across America, other cities are facing the same choices as Boston and New York— =often with less money available to them. States and localities are responsible for more than 90% of America's public water infrastructure spending each year. According to Joseph Kane, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, a think tank specializing in economic and policy research, this means that cities bear most of the financial burden of addressing outdated sewer systems.

"I don't think communities often want to reach the point of a consent decree," said Kane, but "the systems are old, and in many cases the utilities have not had the financial capacity themselves to proactively stay ahead of these repairs."

An EPA grant program that originated in 2018 amendments to the Clean Water Act provides small grants for cities to work on their sewer systems. The 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law brought about another infusion of federal resources, mainly in the form of the Clean Water State Revolving Fund, which funneled $11.7 billion in loans to states, which in turn distributed them to individual utilities. Kane said, however, that this legislation only slightly alleviates the economic burden for states and utilities, which ultimately have to repay these loans.

"It's still just a blip compared to the magnitude of the cost that states and localities themselves are having to bear," said Kane, on existing federal resources for flood management.

The funding from the bipartisan infrastructure law is also slated to last through 2026.

"There are already questions in Washington and across the country that when this funding lapses in another couple years, is there going to be additional support for these sorts of projects?" said Kane.

Several American cities have turned to the imposition of stormwater fees to raise funds for sewer system improvement work. The fees are paid by individual property owners, shifting the costs of flooding prevention onto the community. Stormwater charges are calculated based on the impervious surface cover of the property—those with a higher area of impenetrable surfaces, such as rooftops and parking lots, are charged a higher amount.

In April, the Boston Water and Sewer Commission implemented a stormwater charge that applies to all properties with over 400 square feet of impervious area. New York City has yet to implement any stormwater charges.

"Stormwater fees create a connection for property owners to chip in something for their contribution to the stormwater runoff challenges," said Kane, "but there's a lot of debate on exactly how high these stormwater fees should be, how they're calculated, who pays what."