The rural Americans too poor for federal flood protections

Todd DePriest doesn't "believe in Facebook," but uses his mother's account to surf the website's digital marketplace. That's what he was doing two summers ago when he saw alerts about severe floods in Letcher County, Kentucky, where he serves as the mayor of Jenkins, population 1,800.

Public service announcements warning people to "turn around, don't drown" during floods were circulating on his mother's feed. DePriest got up from his computer to look out the window at the torrential rain and realized the threat his own town was about to face.

DePriest jumped in his Jeep to check on the bridge at the lower end of Jenkins. When he got there, the road across the bridge had already flooded.

"I started calling people I knew down there and said, 'Hey, the water's up and if you want to get out of here, we're going to have to do something pretty quick,'" DePriest said.

His next calls were to the fire department to prepare them for the emergencies to which they were likely to respond, then to city workers to get essential maintenance vehicles like garbage trucks to higher ground.

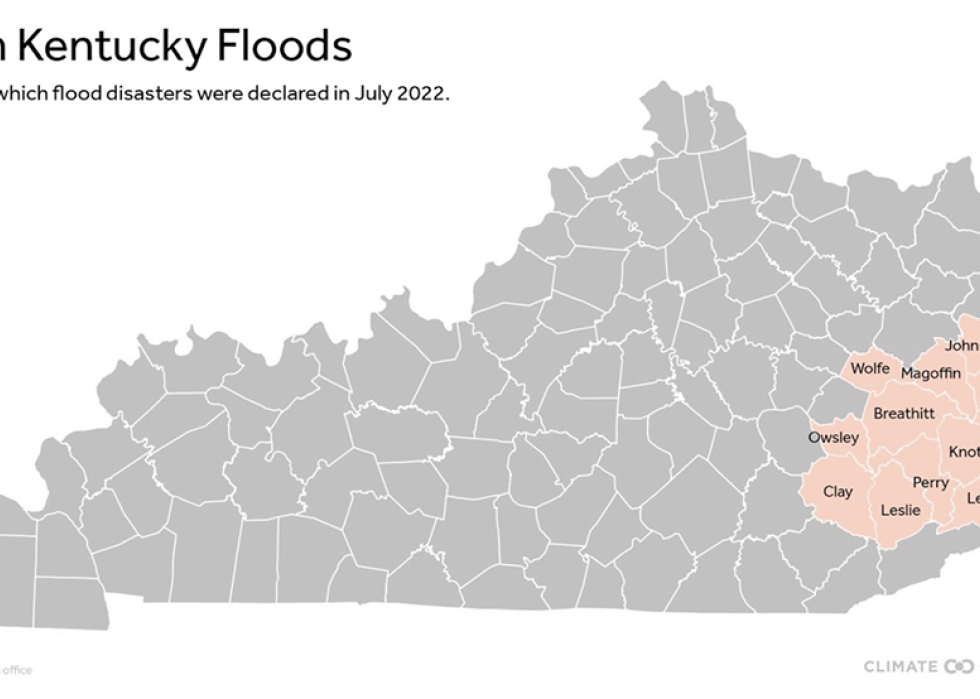

Letcher County was one of the hardest hit of the 13 counties declared federal disaster areas by FEMA. Five of those killed across the region were in Letcher County.

Two years since the floods, the region is still rebuilding. "They (FEMA) were telling us it was going to take four or five, six years to recover and get through this," DePriest said. "And I thought, well, there's no way it's going to take that long."

Now, DePriest hopes it only takes five years.

"All the processes and dealing with FEMA—and I think they're fair in what they do—but it's just a process," DePriest said.

The National Risk Index multiplies a community's expected annual loss in dollars by their risk factor. Like most of the east Kentucky counties that flooded two summers ago, Letcher County's risk level is scored "very low" by the risk index.

That's because it includes annual asset loss in its equations.

Rural counties like Letcher, where the average home costs about $75,000 and median household income is half the national average, score lower on the risk scale because there are fewer dollars to lose when disaster strikes. The area's flood hazard threat is deemed relatively high but the potential consequences in financial losses are lower compared with denser areas.

The urban-rural disparity can be examined by comparing how the National Risk Index judges Jackson, Kentucky, a small city about 80 miles southeast of Lexington, with Jackson, Mississippi, the Magnolia State's populous capital.

Both cities saw disastrous flooding during the summer of 2022. Unlike its namesake in Kentucky, Jackson, Mississippians suffered no flood deaths, though financial damage was far worse—an estimated $1 billion.

Hinds County—home to Mississippi's capital—is assigned a "relatively moderate" risk level. Its social vulnerability is categorized as very high, with community resiliency categorized as relatively high, meaning the community is expected to bounce back more effortlessly after disaster. River flooding is deemed the second greatest natural disaster risk, with annual losses estimated at about $15 million.

To compare, Breathitt County, where Jackson, Kentucky, is located, is given a "very low" risk level by the National Risk Index. Its social vulnerability is categorized as relatively high and community resiliency is categorized as very low, suggesting it would need more help after disasters. Although FEMA considers river flooding the greatest disaster risk to the community, its annual losses are rated at just $1.3 million.

This urban-rural difference matters because FEMA uses the National Risk Index to determine how much money communities should receive to better prepare for natural disasters. For example, it's being used to make decisions about spending $1.2 trillion available to lessen future flood risks under the U.S. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

The risk index is also used to determine which communities get money through FEMA's Community Disaster Resilience Zones program, which designated 483 community census tracts as Community Disaster Resilience Zones last year. This means the communities inside those tracts can receive extra money for disaster planning. Of those census tracts, a third are federally classified as rural.

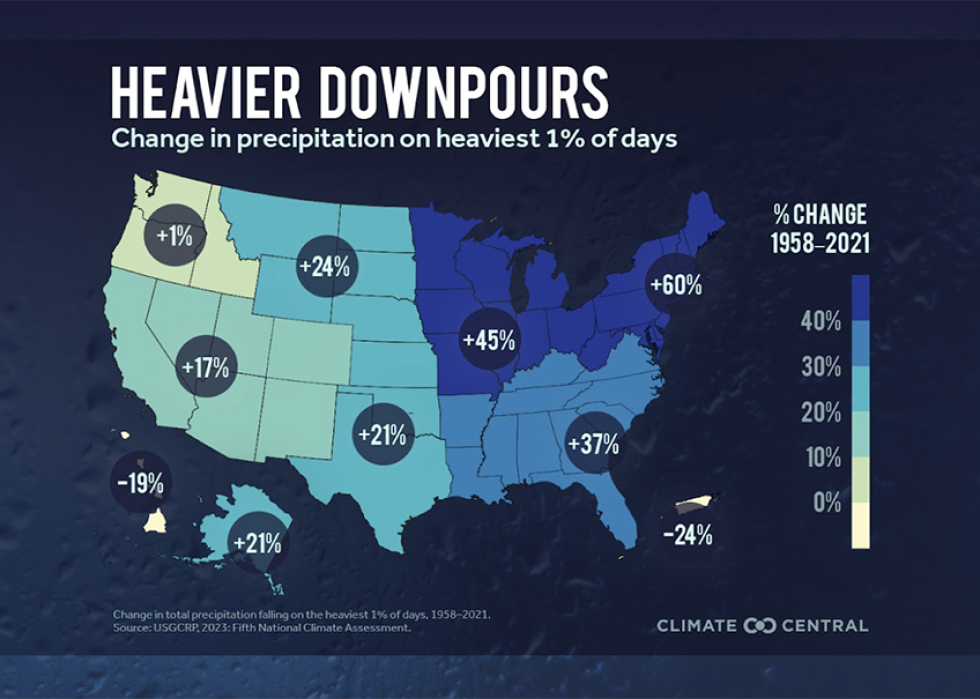

Disaster experts say relying solely on the risk index can disadvantage places that lack long-term weather records—which are often missing from rural communities.

Weather stations can be sparse in treacherous landscapes. Rural areas are among the last to have their flood hazards mapped by FEMA, with the agency prioritizing higher-density regions. And National Weather Service offices tend to be located in more urban areas, according to Melanie Gall, co-director of the Center for Emergency Management Homeland Security at Arizona State University.

"I think that we miss a lot," she said.

Progress Post-Flood

Immediately after the July 2022 floods, FEMA and Kentucky Emergency Management began temporarily providing trailers for hundreds of flood survivors. Both programs have since ended.

FEMA gave trailer occupants the option to purchase their units as permanent housing. The trailer cost was determined by a formula that factored the type of unit, its size, and how many months it had been occupied by the interested buyer.

In the middle of the most recent winter, 18 months after torrential rainfall on steep slopes left so many families homeless, federal trailers that hadn't been paid for were hauled away.

Kentucky's program offered more flexibility: While the program has ended, three families still live in state-funded campers, according to Julia Stanganelli, flood recovery coordinator for the Housing Development Alliance. The Eastern Kentucky-based affordable housing developer has led the efforts to rehab and rebuild houses lost in the flood using state disaster money.

The three families are living in the campers while they wait for a new housing development to be built above the floodplain in Knott County, Kentucky, Stanganelli said.

East Kentucky's population was declining long before the floods. Shaping Our Appalachian Region, a nonprofit focused on population retention and growth, estimates Eastern Kentucky has lost nearly 55,000 residents since 2000. The floods accelerated the losses.

During the 2022 floods, already sparse cell service went out entirely, and even the U.S. Weather Service's on-duty warning meteorologist faced busy or disconnected phone lines, recalls Jane Marie Wix, a warning coordination meteorologist with the Weather Service.

Wix said the creek near her house turned into a "river," preventing her from reaching work. "I don't think I've ever felt so helpless before."

Locals are working to better prepare for the next disaster, with or without federal government help.

Todd DePriest, the mayor of Jenkins, worked with the nonprofit law firm Appalachian Citizens Law Center to pay for four stream monitors that can trigger flood warnings.

Wesley Bryant, the Pike County resident whose home flooded two years ago, said he's called his state representatives "hundreds of times" to keep Eastern Kentucky's disaster recovery top of mind.

Bryant said he recently felt "pretty defeated" after receiving another notification about failing to qualify for federal assistance. But he said he won't quit fighting.

"This is my home, this is my commonwealth," Wesley said. "I'm going to fight for it."